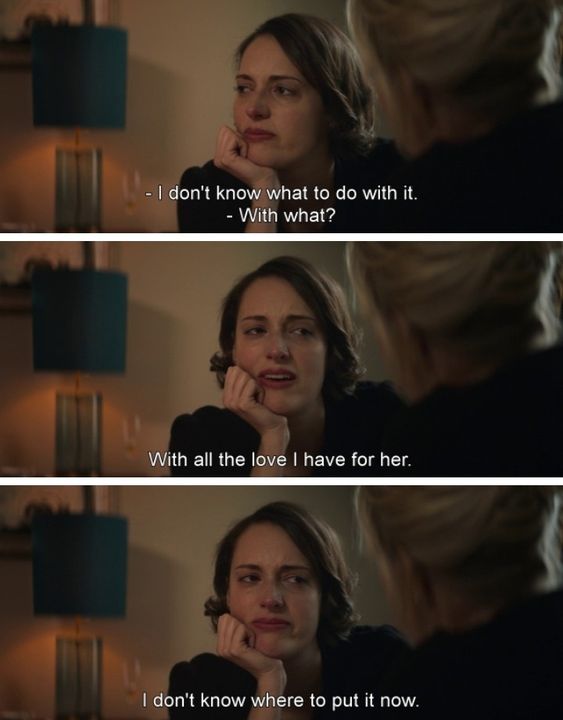

‘Death and Doughnuts’ – Schedule for a Morning of Palliative Care Teaching at Medical School

Note: this post was first published on the Portfolio page of my website on July 25th.

And now, stop.

I have been working on this piece for months now, trying and failing to find a way in. I have a lot of thoughts, but I don’t know how to order them, I don’t know where to begin. I suspect there may be an element of psychological block at play: the topic is one that feels too vulnerable to share.

The reality of it is this: my heart aches.

My heart aches.

I am trying to take a step back, to imagine those words in someone else’s mouth. To hear them spoken and observe how I react. I’m met with judgement. My own judgement. They are words that feel true when written, close to the truth I am trying to portray. But spoken out loud they feel off. Too dramatic, too desperate, too much. They redirect the spotlight in a way that is uncomfortable to me, that feels wrong. But perhaps that in itself is a fallacy.

Grief is one of those words that encompasses such an immensity of feeling and experience. There is the most obvious cause, death, the thing we know we must encounter at some point within our own lives, within our own circle of family and friends, the thing that many doctors will have been acquainted with, however indirectly, by the time we start work. We speak a lot, these days, of how uncomfortable we have become in the face of death. But we are not completely bereft of coping mechanisms yet. There is an infrastructure in place: a process of verification, certification, release. There is an expectation, if not a full understanding, of what will happen. There are systems, even if they feel outdated or somewhat false, to process and navigate the moment: religion and ritual: a funeral, a wake, a prayer. There is a recognition that things for a while will not be okay. That we will struggle. That we may fall apart. And that that is okay.

Far less easy to negotiate, are the quieter more private moments of grief. Tiny shifts in our understanding of how things are – brought to a head perhaps by a chance event, words that struck home, or simply sheer force of repetition, until the alternative, the reality, is no longer possible to dismiss and ignore. That the relationship is over, that it never was true. That the thing you fear most has returned, the thing you could never quite bring yourself to face must be addressed. That you are no different than all the rest. That the things you hoped would be different will not, can not, and were never going to be. That you can no longer close your eyes to the way that others live, or struggle to live. They are realisations dirtied by shame, anger and rage, despair.

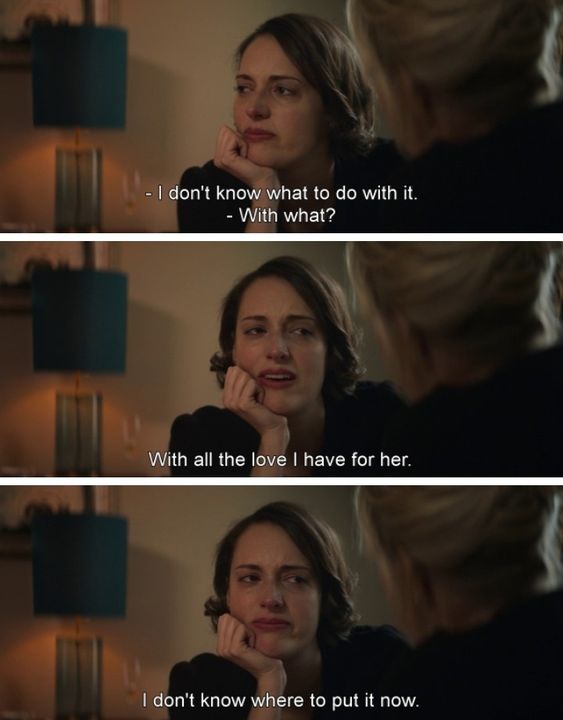

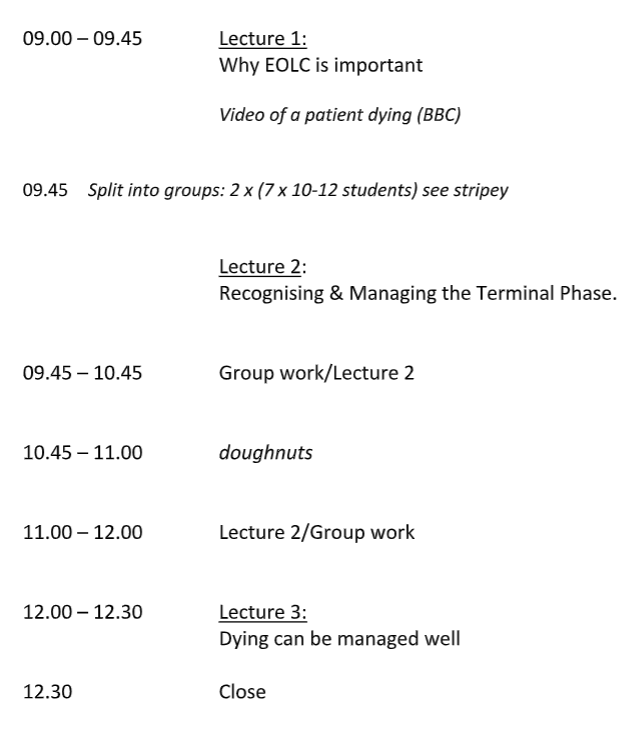

No one ever really teaches you what to make of your emotions. It is difficult to conceive of how such teaching might be designed, emotions being experienced so differently from one person to another. At medical school we learn about death. Death in an objective, scientific way: the terminal phase, the correct dosing of pain relief, the peculiarities of the paperwork. We were exposed to narratives of grief, encouraged to go after them and reflect upon them. But already at my medical school, simultaneously, we were being modelled how to buffer. Every palliative care teaching session would include a break for doughnuts. What of it? Was that not a kind gesture? Was it not comforting to know we could reliably look forward to something nice? Yes, on the one hand. On the other hand: here is a way to distract you from any uncomfortable feelings you may have. Train your brain to associate sadness with sugar – when you’re sad, you will reach for sugar. It is a good way to blunt, it may blunt enough to allow us to bury whatever came up. I think most of us were drawn to this trick of the trade. We become adapt at buffering, we find our own personal ways. But it’s not a long term solution, the emotions don’t go away.

The thing with medicine is that you encounter grief every day. Patients die. Sometimes fast, before you’ve had any chance to get to know them. Sometimes slow, after you’ve cared for them for days, weeks, years. Death is escapable, after a while. If you don’t wish to have much to do with it, you can pick a specialty, a sub-specialty that will evade it. But as long as you are working in contact with patients, you won’t be able to avoid grief. Multiple times per day, patients will experience loss. Aspects of their health and independence are taken from them, things that make up their identity, their future, their sense of self. The things for which there is no recognised script, the things none of us know how to handle. And as physicians we bear witness to this every day. ‘It’s Shit Life Syndrome’, a doctor I worked with once told me. ‘There’s nothing you can do about it, it’s quite depressing’.

tell me the truth: the energy goes somewhere

Vana Manasiadis, The Grief Almanac: A Sequel

How have I handled grief? Poorly, I think, on the whole. If I learnt one thing in my early twenties it was how to compartmentalise what I couldn’t face. I came to recognise the emotional outcome of a situation before it had fully developed, I knew exactly what to anticipate, how to deflect, distract, box up, move on. It is a skill that has served me well. In fact, I don’t know how I would operate without it. Patients want sympathetic doctors, yes. But a doctor awash in their own grief is no use to anyone. Compartmentalising may actually be the only way to get through the day, at least in the earlier stages of training, when you have so much less control over what the job involves. But after a while things begin to spill over, to spill out. Grief will wait, but it doesn’t go away.

Almost instinctively I learnt how to buffer. Binge-watching TV series, eating chocolate by the bag. Over-exercising, taking on the next challenge: there’s always another exam to be done. The coping mechanisms are finite, most people have a handful. You barely need to get to know the people you work with to understand which are theirs. You can even attempt to balance them out: a kind of messed up mix and match: you can overeat sugar and spend hours in the gym. And it works. For a while. Dull the emotion, cover up the pain. Some people, I imagine, could make it work for ever. It’s a juggling act: of course the brain realises what you’re doing, but there’s always a new distraction to pick up, a new goal to aim for. And if all else fails, the internet is there. Scroll, scroll, scroll. You know the deal.

The breaking point for me came early enough – before the end of my first year of work. And then it came again, over and over, in those multiple tiny experiences that make up an understanding, until the epiphany strikes: I can’t do this any more. I can’t go on like this. This is destroying me. This will break me. I would go for months without feeling any of it at all. And then all of a sudden it would rise up, and overcome me. Under the hot water of a shower at the end of an exhausting shift, when I paused to catch my breath an hour into a demanding run. All of a sudden I would be bent over, winded, gasping for air, as the full intensity of everything I had trampled down rose inescapably to the surface.

The act of living is different all through. Her absence is like the sky, spread over everything.

C. S. Lewis, A Grief Observed

Once I let myself name it for what it was, grief was everywhere. It was a pensioner in heart failure, telling me she was wheezy because she couldn’t afford to heat her bedroom at night. A gentleman waking up from a stroke, unable to talk. A lady with a fractured hip, clutching a shiny red snakeskin handbag to her hospital gown, knuckles white, refusing to accept she would never live alone again. It was the partner of a patient with a severe chest infection, watching their lungs falter, their blood pressure fall. It was the mother of a child that never made it to term, clutching at her stomach as cramps set in. It was any number of young adults with hearts broken from rheumatic fever, of children with asthma sleeping in bedrooms black with mould, of the relatives of patients to whom you have to lay things out: that this is it, the time has come.

I tried to talk to others, to family, to non-medically trained friends. And found myself utterly unable to articulate what I was feeling. I lacked language, that much was clear to me. Whether I had ever possessed it, whether I had lost it, was less clear. But what I rapidly learnt was this: non-medics can’t understand, and I don’t have the words to make them understand. Medics get it. A single word can evoke a infinitude of personal experience: ED corridors, night shift, PPE, winter pressures. There is no need to explain, you look at one another and you just know. But how do you begin to process things that you can’t name, that you can’t explain?

When I started to try, I found there was no easy way in. Perhaps I should have expected that, after years of repression. But without language, which is my main tool of processing experience, how do you draw something out, how do you go within? I found myself at the end of long days and busy shifts knowing that I needed to give space to something I had witnessed, and yet finding it impossible to break down the walls that I had so successfully, unconsciously, erected.

The first entrance I found was pain. In a replication perhaps of the initial breakthroughs: that it takes something to throw you offguard and expose the weakness. I would stand under scalding water until I broke down in tears, run for hours until I could finally cry. Then I learnt that the same effect could be achieved by doing yoga, something at that time so foreign and new that it demanded all of my concentration. ‘Take Foot and put it on Thigh’, the instructor would say, and all of a sudden a rush of emotion would knock me flat. Driving, I found, was another, and cooking, and photography – activities that draw upon a different part of the brain, allowing another part to let go. As the emotions came flooding back, learning how to grapple with them, I turned instinctively back to childhood comforts: stories, books, films, music. Art has become a means of catharsis, in a way perhaps that it always had been, but now more consciously so. More recently I have begun to learn to intercept the process at an earlier stage, before I box it up. I find myself craving something sweet and recognise the urge for what it is: a means of comfort. ‘What’s going on for you, love? What making you hurt?’. I try to stay with it for a moment, to feel the weight of it in my body. And my heart aches.

My heart aches.