From the broad to the very specific. Last month I wrote about the ways in which medical encounters can be shaped by the written word, remarking upon the fact that for something that has such power and lasting impact (with the advent of electronic notes, these narratives can follow patients indefinitely), doctors receive surprisingly little training. Today I’m stepping away from the patient-physician relationship to focus on a very different aspect of language in the workplace: words that give licence to dream.

There has been a lot written about the relationship of arts and medicine. I have worked and trained in a number of hospitals which could almost be compared to galleries such is the richness of paintings, sculptures, poetry on display. It has been well established that patients and staff both benefit from an environment which seeks to celebrate the arts.

I have not been able to find much in the medical literature to suggest a similar relationship between language in the workplace and well being. But in the field of linguistics it has been clearly shown that the language that we speak modulates how we think. It follows intuitively that the way in which we categorise aspects of our workplace can predispose us positively (or otherwise) towards them.

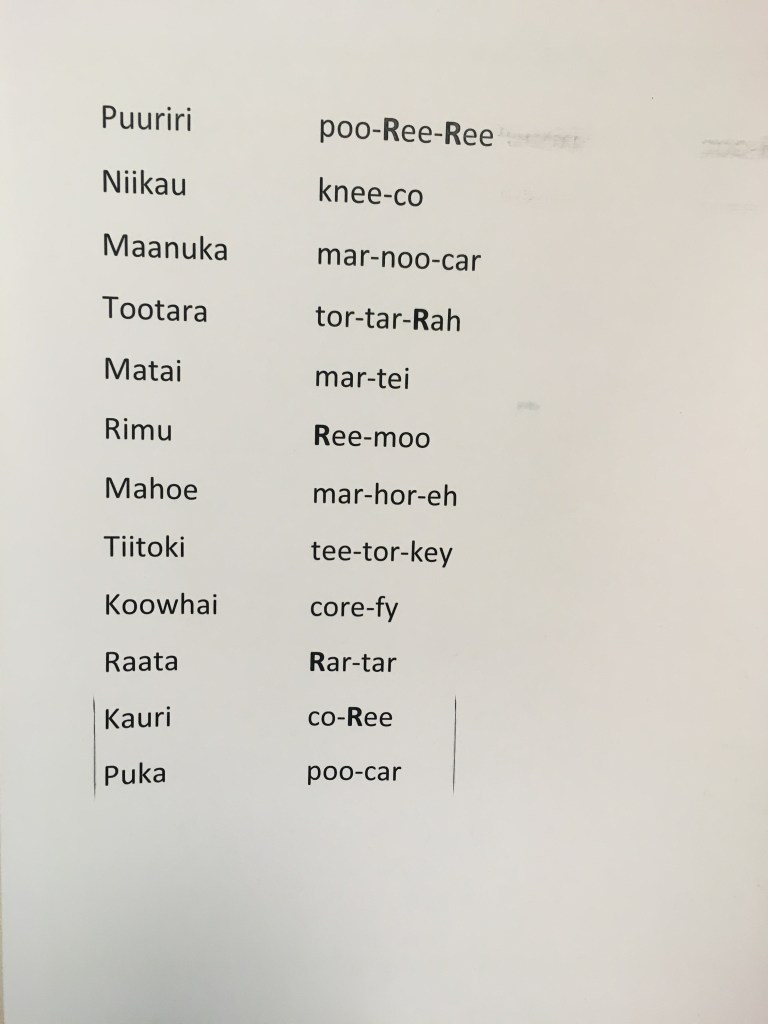

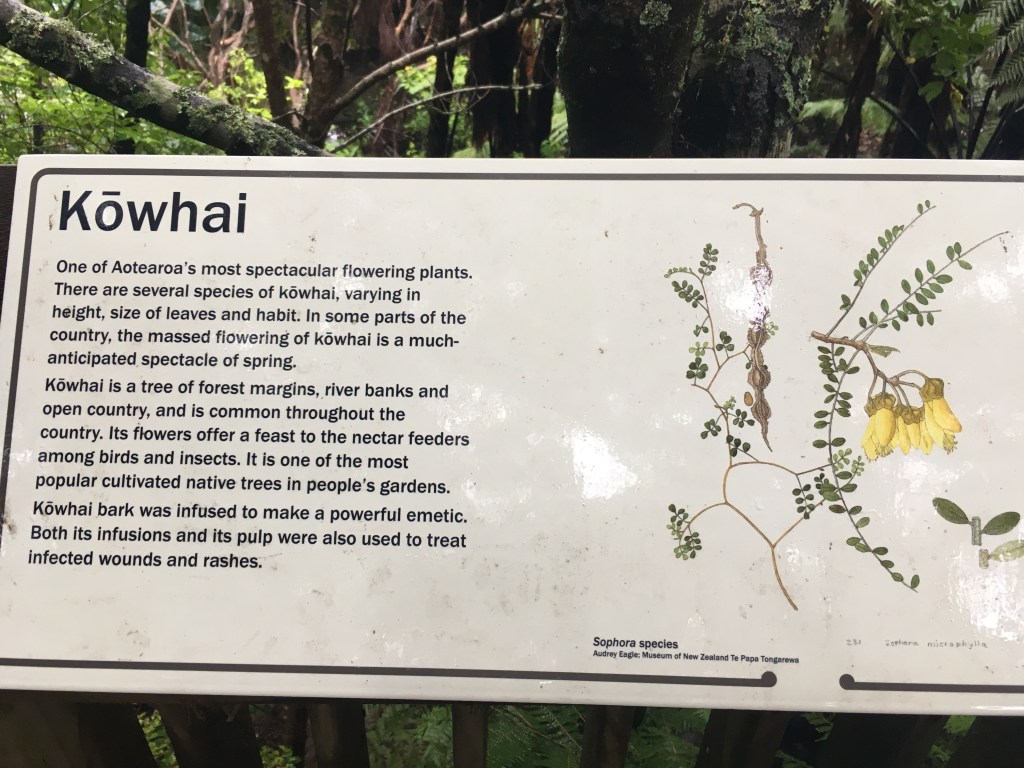

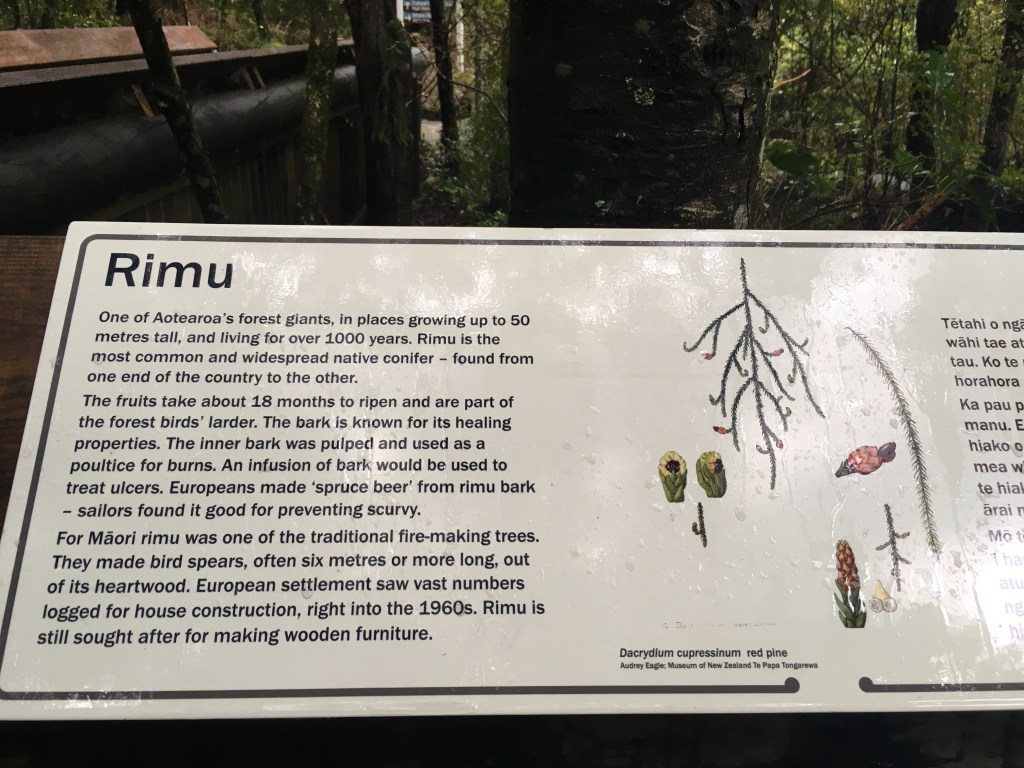

When I started work as a first year doctor, I did so in a district general hospital where the wards were named after local place names. Steepholm, Kewstoke, Harptree, Draycott, Cheddar (after the gorge). Seashore, not unreasonably, was the paediatric day unit. Uphill, surely not coincidentally, was the rehabilitation ward. When I started work in New Zealand, I did so in a hospital where the General Medicine teams were named after native trees: Niikau, Mahoe, Koromiko, Raata, Tootara. At first, these were nothing more than exotic-sounding words to me, contributing to the general charm of being in a foreign country. But as I have lived here and come to recognise some of the trees that they represent, they have come to mean a lot more.

I would imagine that the affective impact of evocative labels differs significantly between people. Not everyone will find their mind drawn inexorably to open landscapes and canopies of trees. But it would not surprise me to learn that the practice of using such a lexicon contributes to workplace wellbeing. Whoever made the decision to name those wards after places and those teams after trees has been responsible for introducing insensible doses of beauty, wildnerness, joy and dream into my life every day that I have worked in those hospitals. It all adds up.